C R I T I C A L W R I T I N G S

|

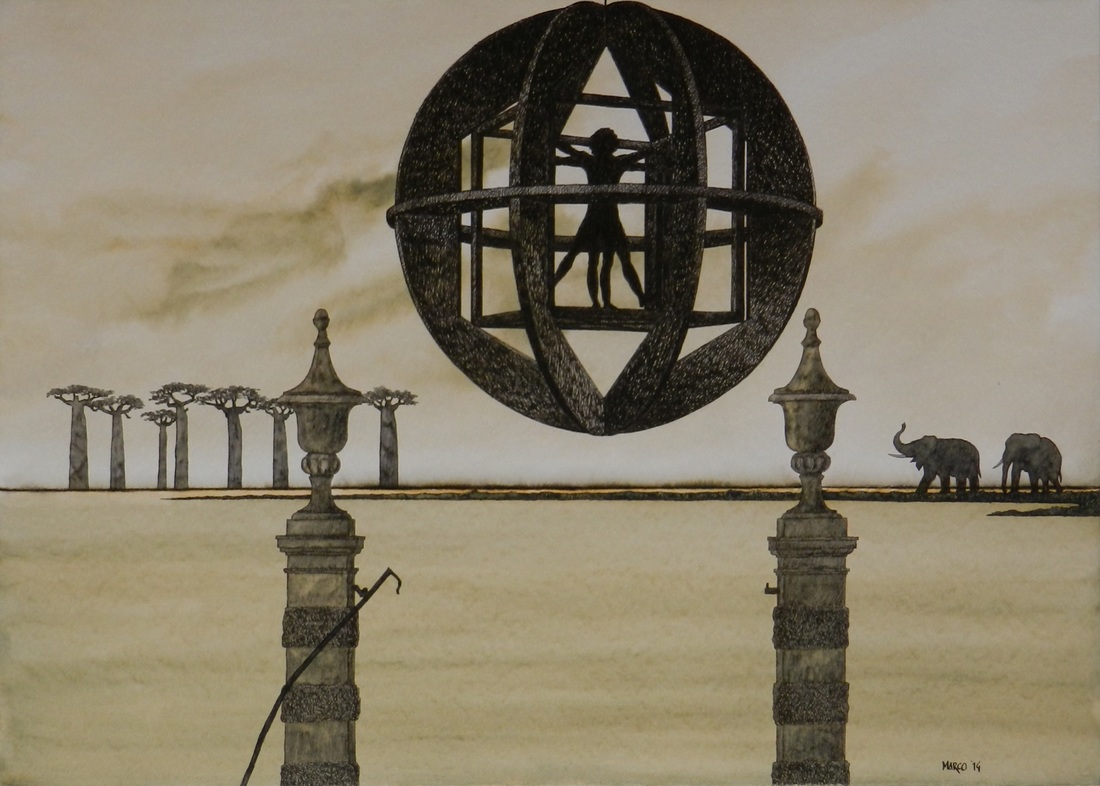

THE COLOURS OF BLACK

Introduction (*) Rosellini's long-term commitment to art has qualified at its highest level only in the last years, starting from 2013. It is no surprise then that there are few exegetic contributions to his work. Two of them, the ones by Licio Damiani and Fabio Franzin, start from the same point, that is he surprise of who, appointed as a member of the jury of a painting Award, is unexpectedly faced with an artist of very peculiar technical characteristics. Such a happy coincidence has resulted in two essays which, even if not strictly scientific, for some kind of "sympathy" in the etymological sense of the world, have sensed very much of the spirit and personality of the addressee, giving priority in their close examinations to their artistic compliances, even if developed in different fields. They have, for instance, sensed the content sources of Rosellini, full of learned references but developed at defined personal speeds. They have moreover outlined the poetic and even musical echoes contained in some glimpses where the physical view expands to a pagan spirituality approaching the absolutization of the items being looked at, between gnostic tradition and eastern influences. From the few but very accurate works of his repertoire comes out a long singing, a kind of metaphysical meditation which turns the materiality of the depicted elements into pure ideas. That was perfectly sensed by Fabio Franzin when he pointed out how «Rosellini's work, apparently figurative, gives a speech which from the tangibility of the real moves to an imaginative which coming close to the wings of the dreamlike, opens to an ″elsewhere″ which cam be palpable, while keeping its slippery elusiveness intact». Less concerned on a personal level, Licio Damiani dwells with subtle remarks not as much on the general framework of Rosellini's work, but rather on the specific works, which he observes in their concrete visibility, for instance The Giudecca Canal, in a way that could not be done better: «Amazing, in The Giudecca Canal, is the front painting between the bright tugboat and the iron boat painted on the lagoon stretch closed on the right, in the distance, by the tower of the Molino Stucky. A dazzling light shines on the water, a wide ray of a setting sunshine opens wide in the cloudy sky. The moving of the two crafts towards the viewer has got an epic rhythm, it recalls with a monumental structure a powerful singing of the sea». Lorena Gava, after a variety of interesting observations, concludes her critical contribution with a summarising remark: «Marco Rosellini proves a skillful technical and compositional control, a repertoire of images, always measured in tone, never yelled and capable of impressing, of suggesting continuously new horizons of sense and knowledge sharing». The substantial uniformity of opinion of the three authors is not only very rare but also a strong evidence that Rosellini's artistic personality is so noticeable as to appeal to whoever coped with it so much to be affected by a fascination conveyed later in their writings. In any of their lines we are lucky to have to read none of the common places which keep at present being rampant in the remarks of mediocre critics: no apathetic use of ″emotions″, word which cannot be found here, and of ″chromatisms″, and this is probably merit of the painter who has got a very peculiar relationship with colour, so much that we could define it as monochromatic variations. After all, the critical approach to be adopted, when regarding Rosellini, starts from the identification of a personality withdrawn in his expressions and extremely firm in his convictions. It is around this centre that revolves the varied manifestation of the different achievable choices which lead to a single inspiring centre, sensed by Novalis, that is the «melancholy of shadows», that state of spiritual «overexcitation which allows to see the reality of things undistorted by the sun splendour, able to create shadows turning a pygmy into a giant». The German poet added that the reason in every religion there is the sun celebration is because the meridian star blinds and prevents the use of reason and concluded: «...it is clear that poetry (and painting to which poetry is linked) does not have to raise affections. Affections are simply something unpleasant like disease». In the paintings of the Venetian artist there are no false giants but the minute essential nature of precious details which go from their physical whole to the spiritual unicum. The tendency to observe the Eastern world has clearly induced Rosellini to paint with his eyes also on aesthetic concepts far from Western rationalism and he must have undoubtedly observed that the scroll of a Chinese painter or, albeit in a different way, Japanese, actually is a kind of meditation before turning into an aesthetic act. To sum up, a sort of plea which accepts the immanence of a pantheism which had been a line of study of Hellenic Neoplatonism later picked up by Gioacchino da Fiore and forwarded to Renaissance, and also in debated papers of Nicola Cusano. For sure that had been a substrate of the works of Leonardo da Vinci who, no coincidence, is celebrated by Rosellini in a particularly interesting ink. We are faced with a delicate production, not only because entrusted to paper and to inks easily perishable but also because influenced by the aesthetic-cultural horizons from where it comes from. When analysing an artist's production, the first concern of a critic is to set him in a stylistic context, something impossible in the present case. If in fact there is no doubt that the painter acts on the basis of realistic criteria, it is also clear that his intentions are not descriptive but interpretative of reality. For him in fact it is prevailing a facies in the midway between realism and abstractionism, the opposite term of a decade-long querelle between who claimed, like Picasso, he could reproduce only the visible and who theorized, like Mondrian, the existence of infinite worlds beyond the visible. Rosellini's solution is peculiar. He is fascinated by the view, caught in carefully studied cuts, and the many significances attributable to the world of intelligence, in the Latin sense of ″comprehension″. It is not a matter of cataloguing but of profound reading. In other words, we need to understand what the artist means in every painted paper. Basically, it is about penetrating the depressed sense of nature with its shadows, the lights off, the mystical silences; and in this regard, there is somebody who has rightly mentioned The Isle of the Dead of Arnold Böcklin and could have reminded even more appropriately the Landscape with a Castle in Ruins or even the hallucinated symbolism of Franz von Stuck. But Rosellini has got other resources which are the ones of the flowers in which lives on the spirit of ancient Chinese painters and his rhapsodic intrusions into subtle cultural contexts which he gets into with the spirit of those who, aware of the limits of his own humanitas made of intelligence, of rationality and curiosity but also of sweetness, finds himself, staying out of the images, in the same position as the characters of many paintings of Caspar David Friedrich: people as solitary and perplexed as heroic on the hedge of a rock facing the immensity of the sea, witnesses of the turmoil of titanic forces shattering the eternal ice or in front of an abandoned cemetery. In the images included in this catalogue, given for granted the technical excellence of the author, the subject for discussions is arranged in several topics which are an artistic corpus and an intellectual autobiography at the same time. The privileged subjects are essentially two: a more realistic one which includes the weather and the atmosphere of Venice and the Delta. Among the Venetian views, it turns out to be interesting Venetian Magic (Magia veneziana) whose title was probably inspired by The Flying Carpet (1880) of Viktor Michajlovič Vasnecov where Rosellini found out the precise quote of the flying carpet he put on the lagoon. The second research point contains instead the excursions to other words and to orderly fantasies addressed to themes which find in René Magritte, addressee of a homage, a point of reference, from which are kept out a bunch of inks regarding the human condition, driven by the desire to know and detained by pillars of Hercules that can be overcome only by imagination and sips of hope. The three Mistletoes (Vischio 1, 2, 3), Lights and Shadows (Luci e ombre) and In the Woods (Nel bosco) belong to the first group, in the first section; in the second one, the nine papers dedicated to Venice, in the third the five ones illustrating the Delta and the Stones (Sassi), a work of distorting realism. The second group is composed of few extraordinary works linked to common lines of research or of unique items like the essential and linear surrealism of Autumn Riflections (Riflessioni autunnali), an ink which makes a clear contrast between the dead leaf on the chair and the vitality of the young girl who is represented upside down though. Of great interest are the works showing signs of a possible intervention from a mysterious sky and which involves some hot air balloons recalling the Golconda by Magritte with its many little men coming down from the sky. As significant is Ciao Magritte, which is a quote of Le chateau des Pyrénées, based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe and which in Rosellini's version does not float in the air by its own virtue but it is held up by a hot air balloon, an image dear to him and which shows up again in Presences and in The Pillars of Hercules, always as a symbol of the relief needs of man to understand the world around him and exorcise his peculiar restraints. A special value has to be conferred to Leonardo, not just because of its execution but because of its setting up as quintessence of humanity according to the metaphorical values contained in the drawing where the great Renaissance master gave shape to the thought of Nicola Cusano about the essence of the individual, somatically perishable and animistically eternal, since his soul is of angelic kind. Here, as stressed by the contemporary artist, in including the drawing of the Vitrurian man top of the pillars of Hercules, the symbol becomes transparent: the union of the square representing the Earth and of the circle which is symbol of the universe heightens the perfect nature of the divine creation which guarantees the link between art and science, not to mention that the elephants on the horizon remind that, according to Buddha, this animal stands for wisdom. Odissey, in similar figurative terms, traces back to the same ardour for knowledge, while Fantasies at the Vittoriale, the princely residence of Gabriele D'Annunzio, is a divertissement which , with an uncommon chromatic sparkle, recalls the protagonist of a season of Italian history and custom, caught in a sort of romantic relationship Tod und Leben represented by the plane of the brave pilot and at the bottom a recall of The Isle of the Dead of Böcklin. Rosellini's work takes an eccentric position, compared with the present overview of figurative arts, for being representative, in a world where crying and showing off prevail, of an attitude laudably démodée. Aldo Maria Pero (*) Introductory text for the monograph "Marco Rosellini - The colours of black" by critics of Licio Damiani, Lorena Gava and Fabio Franzin. |

Aldo Maria Pero graduated in Arts and Philosophy at Genoa University, where he started his university career which ended at Berkeley University of California. He was a Lecturer of Modern Art History at Genoa University, Visiting Professor of Italian Art History at the Sorbonne in Paris, Tenured Professor of Contemporary Art History at Heidelberg University, Visiting Professor of Contemporary Art History at Ann Arbor University of Michigan, finally Tenured Professor of Contemporary Art History and then Deputy Director of Art History at Berkeley University of California.

Back to Italy, in 2010 he founded the XXI Century Art Movement and the magazine with the same name. At present he is a very active curator, art critic and art event promoter in Italy and abroad. He lives in Savona. |

|

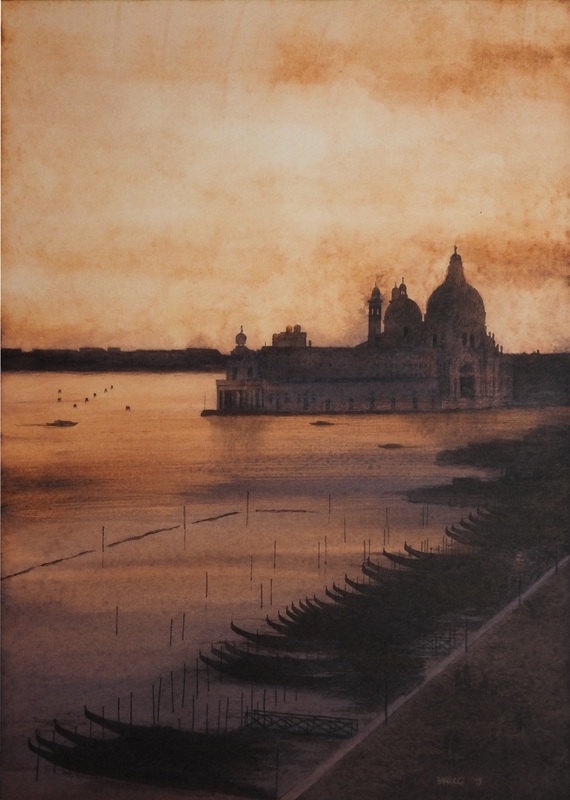

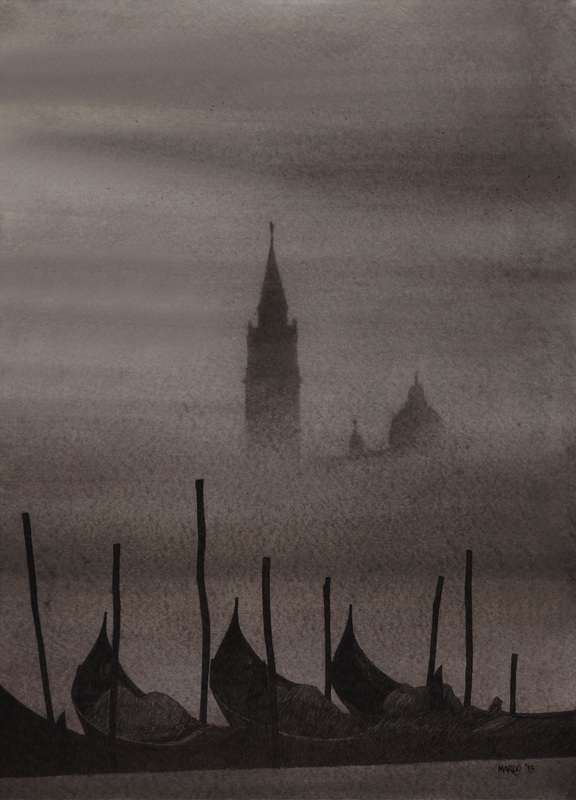

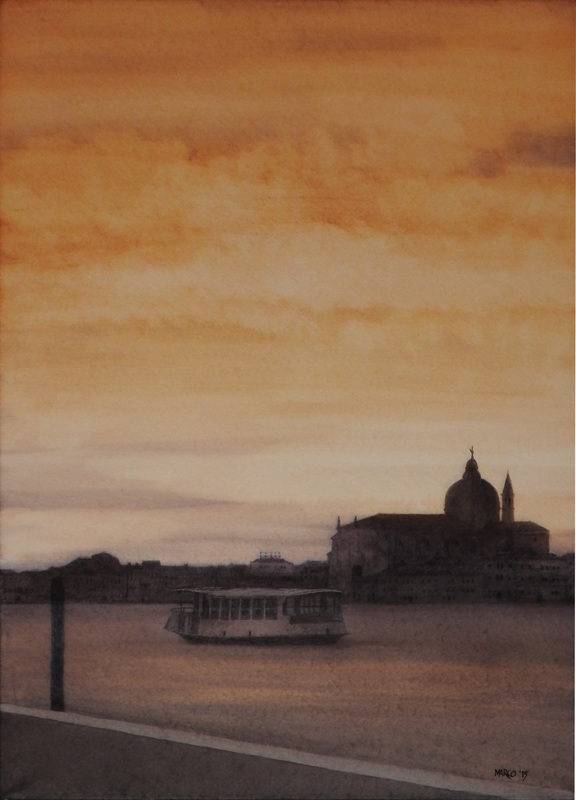

Lagoons and memory

When I think of the paintings by Marco Rosellini, I think of a poignant universe, melancholic and nostalgic. I don't know id that is because Venice often appears at the sunset or shrouded in fog with dark gondolas and architectural grey-coloured scenarios. It is a fact that a zenith light is very unlikely: a twilight filled with evenings shadows and night profiles is dominant. Even when you can take the lagoon and the sandbacks at a glance, you won't miss the ashen horizon of land, sky, water. That is surely due to the choice of the black chromatic inks, unusual technique which allows to create a stimulating variety of monochrome, worthy of the ancient grisaille and able to astonish with its trompe l'oeil effects. I am thinking in particular of the masterful creation of the The Delta at Comacchio (Il Delta a Comacchio), where the broken and discontinued net forms a moving board of incredible accuracy and concrete form. Marco Rosellini creates clear perspectives, the firm and confident stroke outlines always identifiable profiles. The depths of the background, the extended spaces, are frequent and, in my opinion, particularly fitting are the incursions into amphibious territories linked to half-abandoned mash-plains where it is possible to trace some human evidence by a few but charismatic elements like the rubber boots hanging on upside down in Until Tomorrow (A domani). The areas of still and stagnant water fed on poor and weekened vegetations usually emerge from the omnipresent horizon line, preventing any flaking and possibility of abstraction. There is an alphabet of recurrent signs, a grammar made of essential elements reduced to a minimum: a leaf, a branch, an emerging bit of land, represent now and then the ingredients of a mystic vision, interspersed with semblances and projections, which hardly resists and survives within the logical framework of the representation. The longing for mystery, of the unseen or unspoken, is the intriguing and engaging aspect of the chosen portion of the world, of the objective score standing as a symbol , as an inner condition full of lyricism. Very often the artist makes use of visual synecdoche, where the portion and the detail take on a strong and all-absorving suggestive significance from which you can deduce the preference to objects, to the loved architectural tracks which become improvised scenarios or even metaphysical and surreal inventions of exotic and desert natural landscapes. So it happens that imaginary hot-air balloons crowd the skies taking now and then the consistency of a compact rock with a Magritt flavour, suspended in the air emptiness of feeble and evasive lives. Recently a magic carpet (Magia veneziana, Venetian Magic) has turned up, fairy tale memory of an East which Venice knows very well and welcomes to the thick steams of its mist together with a Gothic-style bell tower reminding its extraordinary multiculturalism and artistic vocation. Just as recently, the use of black ink subject to specific discolorations has exposed unexpected lights, golden and orange flashes, adhering perfectly to some sunsets whose reflections recall the precious changeable Byzantine silks. Even if lit, Venice remains just as monochrome and monotone, deaf and opaque, confirming an authentic and recurrent stylistic key feature. It could even be a timeless town but the ferry in front of S. Giorgio or the boats in the Giudecca canal lead us to a lively and well-known present but still filled with arcane harmonies and invisible lures. In the long run, these means of transport look meaningless and enigmatic, floating wrappings with no driver, metal offshoots of lagoonal buildings pervaded with silence and almost lowered on the steady water like the hot air balloons hanging in the air (unconscious looking back to desired leavings to never-reached destinations and put into practice only in the imagination and with impossible and imaginary means?). There is always a soft atmosphere, subtle, quiet and controlled. And maybe even the glimmers of light and of sky-blue work like the shadows of the squares by De Chirico, shadows out and beyond any physical time. And what about the wonderful woods spaced by glimmers of light in the dark of dense woodlands, marked by tall and towering trunks like cathedrals erected in the green? And touching is the glare from the sun on the tiny branches, on the leaves archipelagos Japanese-style, fed with the same transparency as the delicate mistletoe vases, profound episodes of still natures extremely selected and lingering in the berries similar to mother-of-pearl fireflies. Marco Rosellini shows evidence of a skillful technical and compositional control, of a repertoire of images always moderate in tone, never cried out and so able to impress, to suggest continuously new horizons of sense and sharing. The persuasive light and dark transitions create surprising timbre chords in which grow cultured scripts, never banal, which flirt with the gaze and defy any indifference because they touch the disquiet and depression of the spirit in the labyrinths of time and memory. Lorena Gava |

Lorena Gava, Arts graduate at Università degli Studi in Padova, art critic and historian, is a teacher of Visual Arts History at the Language School Francesco Da Collo in Conegliano.

She cooperates with several institutions for the curatorship of exibition events and for conferences and courses on Art History. Some of her critical essays can be found in publications and catalogues regarding personalities from the national and international art world. She is an educational consultant of the Art History texts Dossier Arte published in 2015 by Giunti T.V.P. Editori and Treccani. Since 2014 she has been a member of the critic committee of the peer review of Modern Art Catalogue by Mondadori. She lives in Vittorio Veneto. |

|

The enchantment of venetians lagoons

in the inks of Marco Rosellini In the works of Marco Rosellini timeless ideal landscapes come from the deep secret places of the unconscious. Visionary representations of dreams create fanciful visual symphonies. I did not know the artist from Treviso when, last October, I could admire one of his works at the 26th Painting National Award Piero Della Valentina in Cordignano, where I was a member of the jury. The Immagination at the Vittoriale (Fantasia al Vittoriale) had literally fascinated me. The mysterious suspension of the promontory of dark cypresses facing the brightness of Lake Garda, dominated by the glimpse of the royal residence of Gabriele D'Annunzio, seemed to remind me the legendary rhapsody of a literary level and the concise majesty of the sublime scenario with which Arnold Böcklin composed the famous Isle of the Dead. The overflight of a double-winged plane of the 20s emphasised the magic confabulating aura. The artwork routed, in my opinion, by elegance of stroke and by arcane emotional strength, all the other 160 paintings, the 54 watercolours and the 26 graphics participating in the context. Unfortunately, after a lively controversy, even if moderate in tone, with the other jurors, the Fantasia ended up ex aequo in fourth place. In any case, for me it is still a cornerstone. My second meeting with Rosellini's art happened in December at the Christmas Collective Exhibition organized by La Loggia Gallery in Udine. There his fairy-tail Venetian Magic (Magia veneziana) confirmed his magical seduction. From mist held on soft grey modulations emerged a bell tower (maybe the one of San Giorgio, but almost turned into one of the neo-Gothic spires of Molino Stucky ). In the foreground stood out the contours of some gondolas docked at the poles like mysterious visions. High up in the sky a magic carpet carried a loving couple towards some kind of wonderful shores. The fascination of the drawing was such that one night I even dreamt about it. I was eventually offered an even more extensive analysis of an important part of Rosellini's creative corpus in January by his one-man exhibition at Ca' dei Carraresi in Treviso, titled The Colours of Black (I colori del nero). The black is the one of the chromatic inks used (Pelikan, Parker, Lamy, Diamine on Canson Montval paper). Blacks which, treated with decolorants or other reagents, acquire sunny yellow, copper coloured, ultramarine-blue, even glaring white nuances, creating dazzling and mysterious chiaroscuro harmonies. They are works operating sophisticated variations on maritime issues. Ideas taken from a real world, images of memory dreamily turned into ″metaphysical limbos″ as defined by the artist himself. The matching of conflicting elements creates a feeling of conceptual uncertainties, of disquieting silences and of empty spaces suspended in estranging spells. But also a dig in the search for ″other″ meanings in things, of the secret soul shining on them with an alien light. The usual neo-Gothic bell tower and a basilica dome evaporate in the fog, tightened up in the foreground by a line of docked gondolas and they look like coming from a page by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, giving visual image to the notation of the decadent and aesthete Viennese writer himself: «The depth must be hidden. Where? In the surface». A dive, in short, into the existential swirls, stressed by a sort of melancholic boredom, by a light anguish of the inexpressible. The bric-à-brac of figurative elements taken from different cultures, styles and ages, with which the artist stages theatricals, give rise to cryptic images ″in exotic sauce″. The insert of the monolith, taken from the film of Stanley Kubrik 2001: A Space Odyssey on the worksheet with a portal marked by two pillars, ending in capitals shaped like vases with a lid of eighteenth century kind, which hold up an iron gate curtained on the lagoon, restricted on the horizon by a land strip with palm trees, seems to become - quoting the opinion of the film director - the representation of a visual experience «which bypasses the comprehension so to understand its emotional contents in the unconscious». And they are contents which imply - maybe - the turmoil caused by the impulse to wildness in human history. The same stage structure appears in other sheets but with some variations. In the work titled Leonardo, in place of the monolith, a spherical cage citing the wooden sculpture of Mario Caroli, with inside The Man drawn by the master of the Gioconda, breathes in the sky expressing an arcane ambient objectivity. Another one views the inclusion of three hot-air balloons overflying the lagoon, allusive - Rosellini explains - to the caravels of Christopher Columbus heading to unknown lands - on which take shape the contours of two elephants - also meant to be icons evoking the ideal overcoming of the Pillars of Hercules by Ego, Es and Super-Ego. In the distance three hot-air balloons float in the stormy air over three pillars ending in the black light of statues of baroque angels who seem to point at the fatal border of a mysterious ″elsewhere″. The balloons would just go beyond the borders of a merely figurative painting to reach the insidious wastelands of the unknowable identified by the motto Hic sunt leones. The chapter on the Lagune is enriched by other themes. There is the house emerging solitary from the water, maybe the last survivor of a buried village, wrapped in shaken silence, and in the sky a kite carries a touch of a cursed fair-tail. There is the fishing valley with the backlight of the poles holding the nets hung out to dry and the boots of a fisherman, as an indication of a human shadow. There is the giant rock holding a set of houses at the top and looks like it came out from a truculent saga. Another subject called by the artist to animate his lagoon visions is the mention to the Teatro del Mondo designed in 1979 by the post-modern architect Aldo Rossi. Made of wood and metal components, the building, like a raft or a boat, floated in San Marco's basin, between the Piazzetta, Riva degli Schiavoni, end of the Dogana, the Molino Stucky, synthesizing in the layout the architectural theatricality of the Ducal City. Venetian theatre linked to the water and the sky - this is how the author describes it - which repeated in its composition the sea colours and materials, divided into two parts, corresponding to the stalls and balconies contained outside in an octagonal polygon ending in a kind of bell towers or of minaret, and in a square, resting on a raft carrying a texture of images, feelings, memories. Rosellini has included the theatre in a romantic chorale between flights of white waders. On another sheet he has set it up as an essential stage component of an esoteric scene, putting the silhouettes of two characters cloaked in black standing on a Dante's ″vasello″ passing in front of the towering building immersed in a blaze of bleak mystery. One of the two characters appears withdrawn, the other one, standing in front of him, hangs his arm horizontally for a sort of initiatory ritual, on which stands The Raven. In the last two-year-period Rosellini has devoted himself to what we could define ″Venetian ecstasis″. In It is Evening Right Away (È subito sera) the streamer which under a bloodily sunset slides silently in front of the dark outline of the Chiesa del Redentore seems the catabasis of Wagner's The Flying Dutchman lost in a desert melancholy. And, always backlighting, in a coppery Venetian Sunset (Tramonto veneziano) on three perspective planes are painted, respectively, the dark, indistinct set of the Giudecca buildings, the more legible bulk of Punta della Dogana and of the Basilica della Salute, finally, embedded in the right corner of the worksheet, a glimpse of the set of gondolas. A labyrinth of poles, on which shines a lamp-post party, liven up Canals at the Twilight (Canali al crepuscolo), marked at the bottom by linear profiles of domes and bell towers. Wonderful in the Giudecca Canal (Canale della Giudecca) is the frontal match between the bright tugboat and the iron ship, painted on the lagoon stretch closed on the right by the Molino Stucky tower. A glazing light shines on the water , a broad reddish rift opens wide in the cloud-capped sky falling from the dish of the setting sun. The moving of the two vessels towards the viewer has got an epic rhythm, it evokes with a monumental structure a powerful singing of the sea. The composition could have been influenced – according to Rosellini's report – by a painting of Turner, indeed translated with plastic impetus and refined technical virtuosity. The camera cut of these scenographic images, baroque and sumptuous, reminds me, for representational refinement and precious chiaroscuro, the Hollywood films of the 30s Dishonoured, Shangai Express, Blonde Venus, The Devil is a Woman of the German director Josef von Sternberg. Remaining within the film analogies, the daring frame of the pillar with the Leone di San Marco, in the foreshortened pointed arch, has a kind of affinity with the refined representational search made by Orson Wells in Othello or even, going back to the past, with the daring synecdoche of the great Russian master Sergej Ejzenšenstejn, who used to isolate some details to represent the whole, in this case evoking the Gothic architectures on the Canal Grande. All of them are objectified materials which, absorbed and internalised, lead to their symbolist sublimation, in an astonished, amazed, lyrical steadiness. Licio Damiani |

Licio Damiani, after his Law Degree at the University of Trieste, started his career as a professional journalist at the Gazzettino ending it at RAI as Head of Service.

He is the author of two volumes on the 20th century Art in Friuli and of numerous monographs and essays on painters, sculptors and architects. He has made cinema and television documentaries and has published fiction, poetry and travel books. He is a member of AICA, the International Association of Art Critics and writes for newspapers and magazines. Born at Lussinpiccolo, he lives in Udine. |

|

Black whispers

Imagine I say: “This gown is black.” The word “black” in a way is arbitrary. Ludwig Wittgenstein “Osservazione sui colori” Torino Einaudi 2000 The steps leading two human beings, and so two souls, to meet, recognize each other, and therefore get on well together, is very often left to chance. But yet it is true that, if the personal paths (even starting from far away, widening and forking in their uniqueness) move towards one zenith, they can intersect. Then that destiny is helped by the action, the gesture, in which each protagonist is reflected and in which he recognizes himself. So it is for the love epiphany, in which two creatures, until then strangers to each other, open themselves to merge in the most sublime sentiment. So is for friendship. And so is in the matching of the signs which, since the very first glance or reading, evoke something of our own, deep and, sometimes, even unknown. Signum which has the strength to attract and bring two human experiences together. I came in touch with Rosellini's apparently monochromatic art just by virtue of one of the above cases. Two years ago, some artist friends of mine from the town where I have spent most of my life, asked me to be part of the jury of a modest painting award. They are convinced, as I am, that every art jury should not be composed exclusively by the so-called ″experts″ but on the contrary be open to lovers of sister arts as well: musicians, poets, dancers, etc... I accepted the invitation and when we met to examine the submitted works, we had no difficulty at all in deciding whom to award the prize. One work rose among the others, both for originality and quality. Unanimously we awarded the first prize to Marco Rosellini, an artist then unknown even to the handful of jurors who, much better than me, knew the movement of artists who were used to confronting in the regional area both at the contests and the exhibitions. The artwork in question, titled The Lampposts of Via Gera in the Imagination Flight (I lampioni di via Gera nel volo dell'Immaginazione), dotted in black ink on paper, portrays the glimpse of the way to the town church, viewed at night, against a clouded sky, the street lights on; some of those lampposts, for an evocative game, turn into hot-air balloons, similar to Chinese lamps to lift themselves up towards “somewhere else” less compelling, open to a dream entirely to be imagined. I was also given the task of drawing up the rationale. Task which I fulfilled with pleasure and convincingly. I quote it because what was then just a first impression, has subsequently been substantiated when compared with the global work of Rosellini as an artist and, knowing Marco, as a man. «For his poetic and visionary vision and for his capacity to catch sight of the possibility of a rise of the spirit in the evening dark of a village void of human beings. The work of Marco Rosellini, fairy-tale and utopian, where the colour would have looked blasphemous, combines all that with a mature stroke, creative of suggestions and cheering up in so a disquiet age. The work wins over, proving that it is not necessary to search who knows what artifices to create poetry with art: you just need to watch things, sometimes even the most common ones, and be able to imagine something which crosses the hedge of the ordinary». But there was more. In the key feature of the sign of Rosellini, I figured out poetics of mine, which talking to me quietly, somehow spoke about me. It spoke about the boy I used to be, anxious and open to dream, but harnessed in the cultural darkness of a little village, daily holed up in the grime of a shed, between the asphalt close to the church or to the three bars. About the evening lamp which lit up the ink of the words in which I found out consciousness and refuge, first in the books I used to read as to search for my own way, a pass to get out of the more and more oppressive enclosure, later in the ones I wrote, in the ink signs with which I used to fill obsessively the sheets of a notebook, transferred later to the pages of the books I have published, which allowed me to raise myself, to move away from here despite staying, trying to sweep away from the place the beauties stored under the concrete and the asphalt of a North-East all devoted to profit, which grounds goods and soul, blinding the relief needed to survive. *** Other links unite Marco and me. His work with paper and ink, so similar to the work of a poet: same tools, twin vision. Is it just a coincidence that my first real collection of poems was titled The Colour of words (Il colore delle parole) and this first real catalogue by Rosellini is titled The Colours of Black (I colori del nero)? Through poetry I tried to squeeze from words, which on paper are always black, the iridescent juice held within them, when they were extracted from the grass and the moss so dear to me, from a caress or a kiss, as well as from dazzles shining in the dark. Similarly Rosellini, by using black polychrome ink (that is obtained from a mixture of different pigments), proceeding with washings away and rubs with pure liquids like water or aggressive and corrosive like solvents and detergents, separates and extracts the precious chromatic veins or the main artery, the trace of light which the composite black brought together with the other ones. But black still remains prince on Rosellini's papers. As it is on the pages of my books. *** Marco Rosellini gets a little late to the figurative art as a certificate to be presented to the public, but after an apprenticeship, so to say, a lifetime long. Designer and architect by profession, after an accident which has made him voiceless, he confers his message of hope and rebirth to the matching of ink and paper. And it is really amazing what this slim man, with a sunken face which sometimes broadens into splendid and sincere smiles, this man who cannot raise his voice louder than a whisper, has succeeded in creating in just three years time: so short is the time elapsed between his shy drawings and the daring and successful chemical-alchemic search for the work showing here, summary of an extensive and suggestive work which sanctions the originality and quality of his artistic journey. Which seals the esteem and friendship of who writes for who draws, of who puts into words for who paints and keeps silent or, at most, whispers. Between who spells his lines with ink and who whispers a string of poetic signs to it. *** Rosellini's work, apparently figurative, moves from the tangibility of realism to imagination which, brushing the dream wings, opens itself to an ″elsewhere″ which can be palpable,while keeping his slippery elusiveness intact. In his landscapes suspended between water and sky, the two elements which he consecrates as mysterious messengers of a boost towards the shores of imagination and freedom, the black melts into tears, fades into yellow or blue, into green or pink. In his scenic perspectives versus the blue of creation detaining symbols often camp in the foreground: biceps or sherds of restraining nets and fences, pillars with or without gates (close of course), bollards, poles, cordage, barristers, picket fences, jetties or Venetian foundations...but further, between the liquid blue and the impalpable one, always pulsates the hint conveying the thought of a distance (″lontanìa″ quoting Biagio Marin, a man who has conferred an eternal singing to the waters and the skies, a man I feel even closer to Marco's work for themes and figures) also depicted in the pictures of the palm or the baobab, of the elephants, of a legendary and motherly land, origin of life, where the wandering anxiety of this age will be able maybe to find out its sacred bed, its serenity nest. Thought or, better, feeling depicted with the presence of air elements: airships, biplanes, hot-air balloons, kites, birds or suspended rock globes, always caught in a flight that goes, never in one that comes, overflying lagoons filled with slime and sandbanks, partly sunken casoni (country houses) boats beached or anchored at a string wire. As if the possibility of escaping were only in the air element, so heavenly and enigmatic; as if also water, even so cradling, arcane and dear to Rosellini, harnessed the thought in a sludgy seabed, in the march where the slim stilts of the egrets or the flamingos, the only winged beings there, can scamper around, there can surely be no angels or phoenixes running up for a take-off. But who does search for the flight to an “elsewhere” in a land safe and free from the usual constraints in Rosellini's cartouche? It is rare to detect human beings longing for this quiet island. It is the thought. Our thought constrained by a thousand limits, by the trammels of the egotism which keep it low, flat, weighted by the ballast of the useless things we have mistaken for necessary, now so incapable of rising above the rubble of the truth and the miseries that we have so tenaciously and obtusely established. Marco Rosellini whispered this levity to the ink. His specula on paper are the radiography of a body, of a soul which are still capable of dreaming and imagining. He did that for us. And we are grateful to him for that. Fabio Franzin |

Fabio Franzin, born in Milan, moves still very young to the plain of Treviso while the North-East radical industrialization is in progress, first to Chiarano, his father's home town and later to Motta di Livenza, where he lives at present. At the age of 16, he starts to work as a worker in a furniture factory, where he still works.

He publishes poetry starting from 2000s, with a large number of collections, prevalently written in the Venetian spoken in the area of Motta di Livenza, with which he has won many national and international poetry awards. He is editor of the magazine of poetry cultures Smerilliana, and some of his lyrics can be found in several magazines and anthologies. And he is a friend of mine. (MR) |